The Blue Army was a formation that enlisted Poles living in the Americas that were willing to go fight in Europe in the midst of the First World War. It tremendously helped the new Polish state in its war of survival with the USSR.

Origin of the Blue Army

Polish State ceased to exist in 1795 when three major European powers: Russia, Austria, and Prussia (later Germany) split it between themselves. But Polish people and their undying connection to their culture and heritage lived on. Polish artists, engineers, politicians, and soldiers continued to relentlessly work for the Polish cause, either abroad or within the limits of what was allowed by the state. Poles had already some experience in forming their legions abroad – the last time during the Napoleonic era and general Dąbrowski, immortalized in the modern Polish national anthem. But the biggest struggle was only about to come. The First World War saw a sudden crash of the previously immovable European order and many Poles knew that this was probably the last chance to forge a new Polish state, in the midst of fighting between European powers. They were not wrong – and the French were first to acknowledge the opportunity of the massive inflow of Polish military recruits in the war that required hundreds of thousands of soldiers to gain the upper hand.

Formation

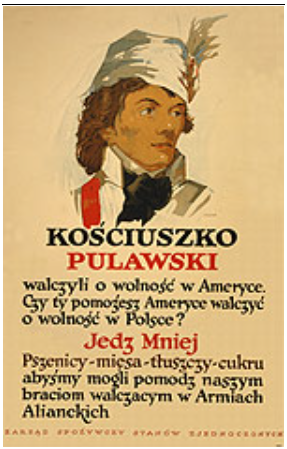

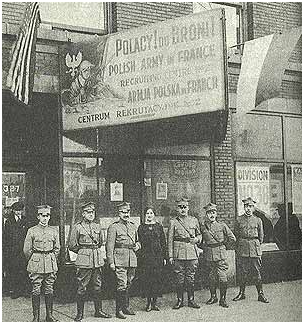

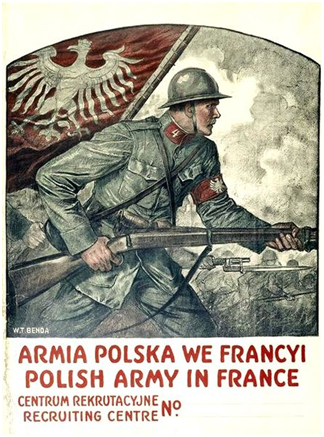

When French president Raymond Poincaré agreed to Mr Dmowski and Mr Paderewski proposal of forming the Polish Army in France, there was enormous enthusiasm among the Polish populace. Poincaré stated: The sons of Poland are coming in great numbers from America to fight henceforth under their own colors on the side of the allies in defense of national ideals…The white eagle of Poland may now spread its wings anew and soar in the radiance of victory. But before that, the first recruitment centers opened on the Canadian side of the border, near Niagara-on-the-lake, with 20,000 joining the force. The United States was still a neutral country and did not join the 1WW until April of 1917. The French were in charge of training and equipping the volunteers – with the significant help of Quebec industrialists, but president Wilson was not enthusiastic about a new army gathering near the border – this was a threat to American neutrality. Soldiers received their blue uniforms which would, later on, inspire the name for the formation: the Blue Army – in Polish “Błękitna Armia”.

Before the US joined the war, recruitment centers opened around the world – Polish people settled almost at every corner of it – they were enlisted in South America, France, and even in Russia, where they also aided White Russian forces against the Bolshevik threat. They swore: before the only God Almighty in the Trinity, to be faithful to my homeland, one and indivisible; I swear that I am ready to lay down my life for the holy cause of its unification and liberation, to defend my banner to the last drop of blood, to keep discipline and obedience to my military authority, and to protect the honor of the Polish soldier with all my conduct. So help me God.

The USA joins the war

But the massive inflow of recruits was only about to happen. When the US declared war on Germany in April of 1917, President Wilson agreed to the recruitment campaign in the United States. There were terms though: the recruit cannot be a US citizen, did not apply for citizenship already, and had no family to take care of. This left single men and women for the draft and the ones that came to the US rather recently because they did not have American citizenship. But it didn’t curb the enthusiasm – from over 38,000 applications some 24,000 were accepted. There were still many of those who escaped Tsarist Russia or Imperial Austria or Germany to the land of the free and now wanted to come back, fight for independent Poland but most importantly, for that Polish motherland to be free and democratic as well. Building American-style democracy in Poland was interlinked with that country regaining independence. The goal was laudable, but unfortunately in the end brought conflict with marshal Piłsudski that had entirely different ideas.

Army arrives in Europe

90,000 Blue Army soldiers arrived in France and joined the struggle. In recognition of this incredible feat, at the beginning of 1918, the Allied powers officially recognized the Polish government (called Polish National Committee) and granted independent command to the newly formed army – as before it was under the command of the French general Louis Archinard. Moreover, President Wilson promised that the peace deal will include a demand to recreate the Polish state with access to the Baltic sea. Because Tsarist Russia fell and left the war after the peace of Brest-Litovsk, the new Polish state could gain not only the lands administered by the Germans and Austrians but also the ones previously held by Allied White Russia. The dreams of many Polish generations were now in reach. As the army was formed rather late in the war, it did not see a lot of fighting on the western front –the major battles took place in Champagne and Vosges mountains with the participation of the 1st Rifle Regiment. But its presence in France was beneficial in the end – many prisoners of war from German and Austrian armies, that were of Polish origin, joined the ranks and the Blue Army grew even bigger. They also joined the ranks of the French military mission to help assist White Russian forces in Siberia.

The armistice

War ended on the 11th of November 1918 and now the chief-in-command Józef Haller had to plan the transportation of his Blue Army to the newly formed Poland. The young country was already in big trouble – war left its land barren and depopulated, there was a famine and diseases spread like wildfire. Germans were slow to withdraw their forces from western-most parts of the Polish state and moreover, they denied the Blue Army entry to Poland via its biggest port Gdańsk (Danzig). Meanwhile, emerging Russian Bolshevik power and the Ukrainian army threatened the eastern borders of the new state. Haller had no choice but to agree to rather an unpleasant railway transfer via ravaging Germany, now in chaos due to the lost war and communist revolution. The train cars were sealed, weapons being transferred separately to limit the chances of Polish soldiers opening fire on this perilous trail. A family member of one of the soldiers, Jan Sumara, remembers his testimony: The trip across Germany to Poland after the Germans were defeated was quite a feat… the Polish soldiers were called the Blue Devils by the German populace…

Arrival to Poland

But finally, they’ve arrived. Major Stefan Wyczółkowski noted: On 15 April 1919 the regiment began its trip to Poland from the Bayon railroad station in four transports, via Mainz, Erfurt, Leipzig, Kalisz, and Warsaw, and arrived in Poland, where it was quartered in individual battalions; in Chełm 1st Battalion, supernumerary company and command of the regiment; 3rd Battalion in Kowel; and the 2nd Battalion in Wlodzimierz. The soldiers were immediately transferred to the eastern front to fight Ukrainians for the control of Lwów and eastern Galicia and Russians for the very independence of the newly formed country. Their contribution to the victory on those fronts was enormous. They were well trained and well equipped, being one of the veteran armies of the 1WW – with one of the soldiers praising the sharpness of the French bayonet in his memoirs. This was in stark contrast to the impromptu military bands that emerged after the war formally ended. But not everything was well.

After its arrival in Poland, Blue Army was merged with the Polish Army and split into smaller units. General Haller lost total control over it, and moreover, not all American volunteers joined the fight. 1,000 of them were demobilized and kept in a camp in Skierniewice, not that far from Warsaw. They were frustrated and bitter over why it happened to them. They were prepared to fight and every single soldier was important in those perilous times. They traveled thousands of miles to help their motherland and their help was dismissed without a word of explanation. To this day many wonders why this disgraceful decision was made. Historians argue that it was simply because marshal Piłsudski didn’t trust them. He feared that they were supporters of his major political rival Mr Dmowski, as he was the one in charge of the previous Polish government in France and one of the most important figures in creating the army. Or perhaps their democratic ideals were not welcomed? One thing is sure – this pettiness left a scar between Polish Americans and the Second Polish Republic. When the Second World War erupted and Poland was once again in dire need of able men and women to fight for her cause, Polish Americans voiced their support but did not trust the government to form a new Polish army in exile. Nevertheless, the relations were not only sour. After the fighting ceased, most members of the Blue Army returned to the United States. Around 7,000 stayed in Poland to help build the new country, bringing a uniquely American perspective with them.

Many notable people served in the ranks, not only of the Haller’s Army but also in other Polish-American units that started their war effort in France. One of the most famous ones was the Polish 7th Air Escadrille, better known as Kościuszko Squadron – named after a great hero of both Poland and the US. In its ranks served a well-known American film director, soldier, and adventurer Merian C. Cooper, who later created his famous 1933 King Kong. He didn’t have Polish descent, although his great-great-grandfather John Cooper fought alongside Polish-American hero general Kazimierz Pułaski at the battle of Savannah. The memory of that was passed from generation to generation and when the time came, Merian decided that it is time to repay the family debt to Poland by joining her fight. He fought valiantly in the airforce and was honored with the highest military order in Poland – the Virtuti Militari medal.

In 2013 thanks to the new biography of German chancellor Angela Merkel the world heard about her paternal grandfather Ludwig Kasner, born Kaźmierczak – also a veteran of the Blue Army. He was a German subject of a Polish ethnicity that switched sides when captured by the Allies in France. This shows that many of Central Power’s soldiers were drafted against their will and joined the Polish cause at the first opportunity. They risked even more than their colleagues from other parts of the world – when captured, they would face the death penalty for desertion. Ludwig took part in both Polish-Ukrainian and Polish-Soviet wars, but then settled in Germany and started a family there, changing his surname from Kaźmierczak to Kasner.

In terms of other interesting stories, there are some photos of Black soldiers wearing Polish military uniforms, which lead to questions as to whether they were African-Americans in the ranks of the Blue Army. Mr Gamski, a Polish amateur historian based in Canada states that they were children of mixed couples – having Polish fathers their surnames became indistinguishable from others and thus their true heritage vanished in the historical documents, which often are only the lists of soldiers from each unit. We cannot be sure whether this is true or not, and since it was 100 years ago the chance to establish that is likely lost forever. They could as well be members of the French Military Dispatch that assisted Poland in her wars – France at that time had a massive colonial empire and drafted her soldiers from citizens all around the globe.

Legacy

Veterans of the Haller’s Army sadly were not treated as such by either Polish or US governments, which definitely left some resentment from Polish American activists, most notably the ones from Polish Falcons – which had an enormous role in creating the Blue Army. Nevertheless, vets honored their service through regular meetings, and parades, presenting their blue uniforms and telling the stories about their war trail. Documents concerning Polish Army in France are still available in the Polish military archives and tremendous work was done by the Polish Genealogical Society of America to index those (https://feefhs.org/resource/poland-army-in-france-records). Their tale should be told with pride, as without the Blue Army Poland’s and Europe’s future would be very much different.