Polish citizenship is quite a modern concept. Although Poland endured for many centuries, starting from the rule of unifier prince Mieszko the first (966), it ceased to exist at the very end of the 18th century. The country was partitioned between three major European powers: Austria, Prussia (then Germany), and Russia. Each introduced its legal system and administrative divisions, which permanently impacted the Polish society and state. Poland only regained independence in November of 1918, after the end of the First World War.

The Kingdom of Poland and The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (966-1795)

In the late medieval and early modern periods, citizenship in the Kingdom of Poland equaled being a member of the gentry class. Only the top 10% of the society could participate fully in the sociopolitical life of the state, including the right to vote in Sejmiki (regional legislatures), Sejm (lower chamber of the parliament), Senat (higher chamber of the parliament), and in the free election – choosing the next king. The ‘citizenship’ rights also extended to property rights and special treatment in terms of the criminal code. Lower classes, such as peasantry and burghers had no such rights, even though they made up a majority of the population. There were attempts to improve the system, most notably the major reform of the Constitution of the 3rd of May 1791. It was too little, too late – and the Constitution frightened Poland’s absolutistic neighbors that the country will follow the steps of France in its revolution against the privileged. Some historians argue that it expedited the decision to partition Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

The partition period (1795-1918)

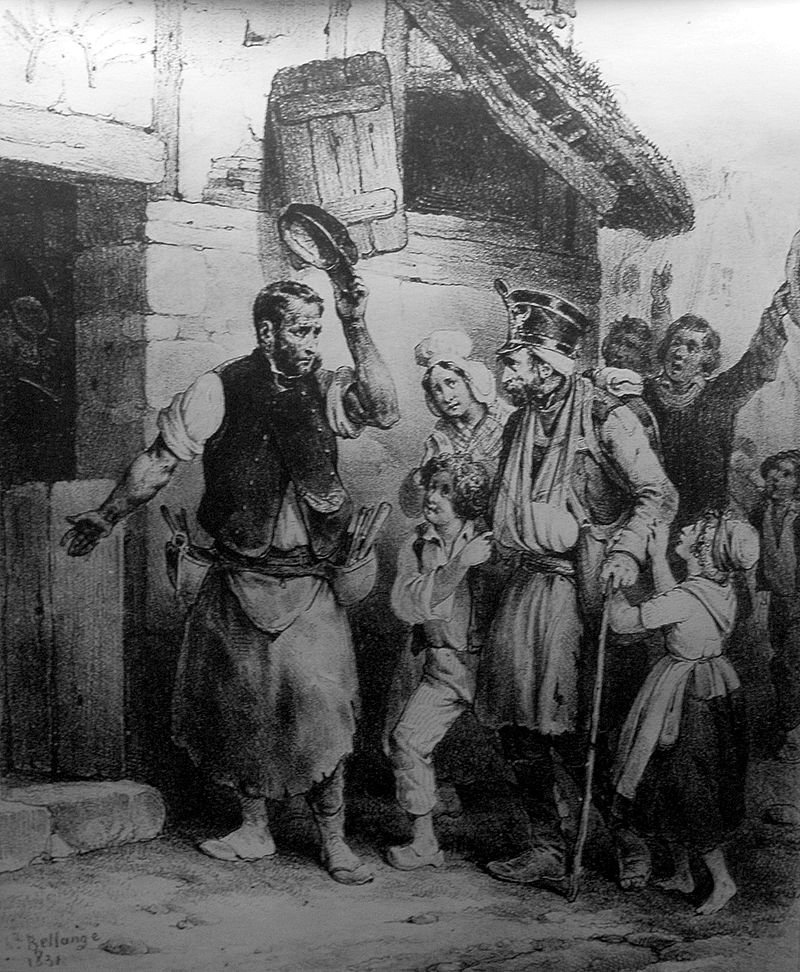

After the Polish state was dissolved, Poles became subjects of either Austrian Habsburgs, Prussian Hohenzollerns, or Russian Romanovs. There was a brief period of Napoleonic Duchy of Warsaw (1807-1815) ruled by French principles and formal equality, but in reality, not much changed. The gentry was still the most respectable group but lost a lot of their privileges after failed uprisings, most notably the November Uprising (1830) and January Uprising (1863). The latter caused intense Russification in the Russian partition – the use of the Polish language was outlawed. The powers that ruled Polish lands had a different approach to treating their Polish subjects over time. At the very end of the partition period, Austria-Hungary was objectively the most liberal one, with its own Polish institutions and members of the parliament.

Over the 19th century the concept of citizenship, as a legal concept defined by regulations rather than just being a subject of a king or an emperor started to emerge. In Austria, citizenship was defined broadly in the General Civil Code (1812) and formally introduced in 1867 when the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary was born. It had citizenship by descent, by marriage, by the acquisition of an official post, or by ten-year residency. In Prussia (then Germany), the first formal legal act on citizenship was introduced in 1842, establishing citizenship by descent. It was later replaced after the German unification of 1871, extending to all citizens of states that were unified. Interestingly, German citizenship did not have the citizenship by residency for a very long time – because there was strong opposition to granting Poles living in the German Empire citizenship. They would fit the criteria, as almost all of them lived in Germany for generations at this point. Without German descent, they were not able to enjoy the privileges of being citizens. Russian citizenship was the most arbitrary of all three. The all-powerful Tsar inherited an early-modern system of treating various groups, based on ethnicity or religion, as his subjects due to various treaties, agreements, or conquest. As proposed in the 18th century, the ethnic Russians most often called themselves ‘Russkie’ and the subjects of the Tsar regardless of their origin were called ‘Rossiyane’. Paradoxically the foreigners were often treated better than natural-borns, as Russian Empire was very eager to attract skilled craftsmen, workers, soldiers, generals, and politicians. This was a cause for complaints by natural-borns, but it was brushed aside. The treatment also depended on the province of the Empire, as in the Far East there was a constant need for Slavic immigration and restriction of Asian one and in the European portion of the country, there were attempts to promote emigration within the Jewish populace. Only at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, Russia started to treat citizenship more formally, due to anti-German sentiment just before the outbreak of the First World War. There was even a procedure of de-naturalization, de facto taking the citizenship away, regulated by the criminal code, but at disposal at the whim of Tsarist clerks. Poles in Russian Empire long had their own statehood called the ‘Kingdom of Poland’ that was ruled directly by the Tsar, in pseudo personal union with Russia. But it comprised only a fraction of former Polish lands and its privileges were cut down quickly. The Polish populace in the Empire was just another group of subjects to the almighty Tsar.

The Second Polish Republic and the Second World War (1918-1945)

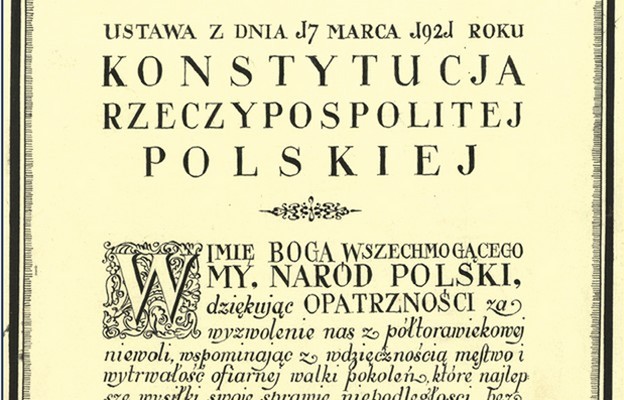

It all changed after the First World War when Poland regained independence after 123 years of being partitioned. The major focus at first was securing the borders of the new Republic. This is probably why citizenship was only introduced 15 months later, 20th of January 1920. It granted the rights to all inhabitants of Polish-controlled territory, regardless of faith, nationality, or gender. That was the starting point of almost all lineages of citizenship by descent, traced from generation to generation to that date. Poles abroad, including in the US, had the option to report to the consulate and have them recognized as subjects of the state. It was not that common and even those who did it, no longer have documents confirming the fact and neither do the consulates. The reality was that most families that lived abroad did so for a good number of years and no longer identified with the old country. Those willing to return and start anew in Poland did that. The March Constitution of 1921 confirmed the full citizenship rights of women and dissolved the privileged gentry class. Nevertheless, there were still some misogynistic articles in the new citizenship law – citizenship of women was treated unequally in terms of marriage to foreigners and naturalization. This is why it is generally harder to confirm one’s citizenship in the female lineage.

The fateful year of 1939 brought an end to the Second Polish Republic, but the citizenship law continued well after the war. The Soviets – now occupying a large portion of the country, complicated the legal standing of many Polish families from the east, granting them citizenship of the USSR. This will later come as an issue of dual citizenship in eastern bloc countries that was resolved unfavorably for the Poles. As per the convention of 1958 dual Polish-Soviet citizens had one year to choose between the citizenships they had, but it was not announced properly in the USSR. As result, they did not choose and Soviet citizenship was the one chosen for them by default. In the German occupation zone, the majority of the Poles had no rights at all. Only the descendants of ethnic Germans, Silesians, and Kashubians had the opportunity to apply for the Reich’s citizenship. This was called signing a Volksliste – and becoming a Volksdeutsche. There were four groups and only the first and the second ones were treated as equals to German citizens. Poland still had a government in exile, first in France, then in London, and continued the legal system of the Republic. The descendants of Polish soldiers of that period have the best opportunity to get the documents needed to prove their descent and rights.

Modern period (1945-now)

The end of the Second World War in 1945 saw major changes to Polish borders. The Yalta conference between Allied and Soviet powers determined that eastern parts of Poland will become part of the USSR and as compensation, the Polish state will be granted parts of Germany – Silesia, Warmia, Masuria, and Pomerania. Poland also became a communist puppet state under the control of the Soviet central committee. The ethnic changes, comprising the forced relocation of thousands of Germans, Poles, and Ukrainians forced new rules on citizenship. Polish People’s Republic first regulated it with minor acts, such as the one issued for the former citizens of the Free City of Danzig, but the new law was desperately needed. Finally, the citizenship law amendment was introduced 19th of January 1951. It brought many changes, as naturalization, army service, and holding a public office outside of Poland were no longer causes of loss of citizenship. It also equaled Polish men and women by removing the misogynistic regulations of 1920. Ethnic Germans, Ukrainians, Lithuanians, Latvians, Russians, and Belarusians moved forcibly outside of Poland lost their Polish citizenship. Their situation was also regulated by later conventions between eastern bloc countries, as the one with the USSR described earlier. All Poles that repatriated, that is, came back to Poland after the war, were automatically granted citizenship. The communist regime rarely took away the citizenship of its citizens, acting purely with political motives. Even so, the modern Polish state does not respect those decisions.

Although there were minor amendments to the law in 1962 and 2012, the main body of the citizenship regulations still remains the same in Poland. Citizenship can be either confirmed by having and proving Polish descent (so-called rule of blood), by the arbitrary presidential grant, or by permanent residency & knowledge of the language. Polish citizenship recently had its 100th birthday and for some time now is also European citizenship. Poland joined the European Union in 2004 and as such her citizens can enjoy all the privileges that come with it. This includes free travel and the possibility to work and study in Europe without any issues. Due to the fact it is automatically inherited from generation to generation provided it was not lost in the process one can be a Polish citizen without even knowing it. Knowledge of the Polish language and residency in Poland is not required. If you have Polish ancestry – be sure to check whether you qualify for the process of confirming it here!